5. Dense Stellar Systems

The sun is a star like any other among the hundred billion or so stars

in our galaxy. It is unremarkable in its properties. Its mass is in

the mid range of what is normal for stars: there are others more than

ten times more massive, and there are also stars more then ten times less

massive, but the vast majority of stars have a mass within a factor

of ten of that of the sun. Our home star is also unremarkable in its

location, at a distance of some thirty thousand light years from the

center of the galaxy. Again, the number of stars closer to the center

and further away from the center are comparable. Our closest neighbor,

Proxima Centauri, lies at a distance of a bit more than four light years.

This distance is typical for separations between stars in our neck of

the woods. A light year is ten million times larger than the diameter

of the sun (a million km, or three light seconds). In a scale model,

if we would represent each star as a cherry, an inch across, the

separation between the stars would be many hundreds of miles. It is

clear from these numbers that collisions between stars in the solar

neighborhood must be very rare. Although the stars follow random

orbits without any traffic control, they present such tiny targets

that we have to wait very long indeed in order to witness two of them

crashing into each other. A quick estimate tells us that the sun has

a chance of hitting another star of less than

There are other places in our galaxy that are far more crowded, and

consequently are a lot more dangerous to venture into. We will have

a brief look at four types of crowded neighborhoods.

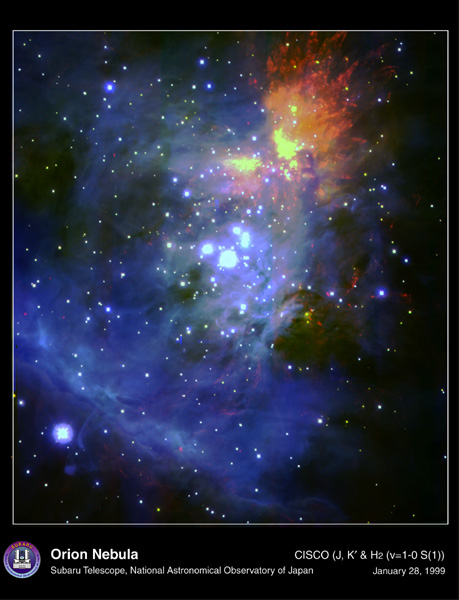

A snapshot of the globular cluster M15, taken with the Hubble Space

Telescope.

In the photo above we see a picture of the globular cluster M15, taken

with the Hubble Space Telescope. This cluster contains roughly a

million stars. In the central region typical distances between

neighboring stars are only a few hundredth of a light year, more than

a hundred times smaller than those in the solar neighborhood. This

implies a stellar density that is more than a million times larger

than that near the sun. Since the typical relative velocities of

stars in M15 are comparable to that of the sun and its neighbors, a

few tens of km/sec, collision times scale with the density, leading to

a central time between collisions of less than

In fact, the chances are much higher than this rough estimate indicates.

One reason is the stars spend some part of their life time in a much

more extended state. A star like the sun increases its diameter by

more than a factor of one hundred toward the end of its life, when

they become a red giant. By presenting a much larger target to other

stars, they increase their chance for a collision during this stage

(even though this increase is partly offset by the fact that the red

giant stage lasts shorter than the so-called main-sequence life time

of a star, during which they have a normal appearance and diameter).

The other reason is that many stars are part of a double star system,

a type of dynamic spider web that can catch a third star, or another

double star, into a temporary three- or four-body dance. Once engaged

in such a dance, the local stellar crowding is enormously enhanced,

and the chance for collisions is greatly increased.

A detailed analysis of all these factors predicts that a significant

fraction of stars in the core of a dense globular cluster such as M15

has already undergone at least one collision in its life time. This

analysis, however, is quiet complex. To study all of the important

channels through which collisions may occur, we have to analyze

encounters between a great variety of single and double stars, and

occasional bound triples and larger bound multiples of stars. Since

each star in a bound subsystem can be a normal main-sequence star, a

red giant, a white dwarf, a neutron star or even a black hole, as well

as an exotic collision product itself, the combinatorial richness of

flavors of double stars and triples is enormous. If we want to pick a

particular double star, we not only have to choose a star type for

each of its members, but in addition we have to specify the mass of

each star, and the parameters of its orbit, such as the semi-major axis

(a measure for the typical separation of the two stars) as well as the

orbital eccentricity.

The goal of our book series is to develop the software tools to make

it possible to simulate an entire star cluster like M15, and to

analyze the resulting behavior both locally and globally.

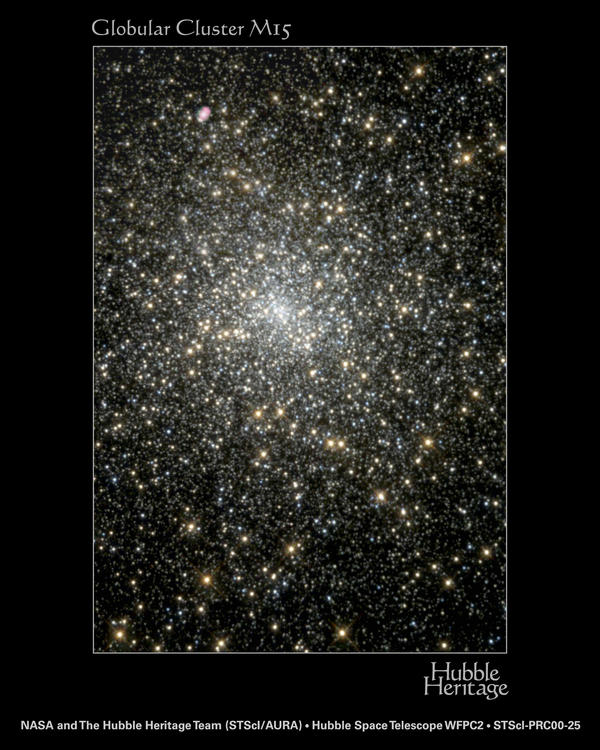

In photo below we see an image of the very center of our galaxy.

This picture is taken with the Northern branch of the two Gemini

telescopes, which is located in Hawaii on top of the mountain Mauna Kea.

An image of the central region of our galaxy, taken with the Gemini

North telescope. The center is located on the right just above the

bottom edge of the image.

In the very center of our galaxy, a black hole resides with a mass

a few million times larger than the mass of our sun. Although the

black hole itself is invisible, we can infer its presence by its

strong gravitational field, which in turn is reflected in the speed

with which stars pass near the black hole. In normal visible light it

is impossible to get a glimpse of the galactic center, because of the

obscuring gas clouds that are positioned between us and the center.

Infrared light, however, can penetrate deeper in dusty regions.

It is a false-color image, reconstructed from

observations in different infrared wavelength bands.

In the central few light years near the black hole, the total mass of

stars is comparable to the mass of the hole. This region is also

called the galactic nucleus. Here the stellar density is at least as

large as that in the center of the densest globular clusters. However,

due to the strong attraction of the black hole, the stars zip around at

much higher velocities. Whereas a typical star in the core of M15 has

a speed of a few tens of km/sec, stars near the black hole in the

center of our galaxy move with speeds exceeding a 1000 km/sec. As a

consequence, the frequency of stellar collisions is strongly enhanced.

Modeling the detailed behavior of stars in this region remains a great

challenge, partly because of the complicated environmental features.

A globular cluster forms a theorist's dream of a laboratory, with its

absence of gas and dust and star forming regions. All we find there

are stars that can be modeled well as point particles unless they come

close and collide, after which we can apply the point particle

approximation once again. In contrast, there are giant molecular

clouds containing enormous amounts of gas and dust right close up to

the galactic center. In these clouds, new stars are formed, some of

which will soon afterwards end their life in brilliant supernova

explosions, while spewing much of their debris back into the

interstellar medium. Such complications are not present in globular

clusters, where supernovae no longer occur since the member stars are

too old and small to become supernovae.

Most other galaxies also harbor a massive black hole in their nuclei.

Some of those have a mass of hundreds of millions of solar masses, or

in extreme cases even more than a billion times the mass of the sun.

The holy grail of the study of dense stellar systems is to perform and

analyze accurate simulations of the complex ecology of stars and gas

in the environment of such enormous holes in space. Much of the

research on globular clusters can be seen as providing the initial

steps toward a detailed modeling of galactic nuclei.

5.1. Galactic Suburbia

per year. In other words, we would have to wait at least

per year. In other words, we would have to wait at least

years to have an appreciable chance to witness

such a collision. Given that the sun is less than five billion years

old, it is no surprise that it does not show any signs of a past

collision: the chance that that would have happened was less than one

in a hundred million. Life in our galactic suburbs is really quite

safe for a star.

years to have an appreciable chance to witness

such a collision. Given that the sun is less than five billion years

old, it is no surprise that it does not show any signs of a past

collision: the chance that that would have happened was less than one

in a hundred million. Life in our galactic suburbs is really quite

safe for a star.

years. With globular clusters having an age of more than

years. With globular clusters having an age of more than

years, a typical star near the center already has

a chance of more than a percent to have undergone a collision in the

past.

years, a typical star near the center already has

a chance of more than a percent to have undergone a collision in the

past.

5.2. Galactic Nuclei