7. Yoshida's Algorithms

Bob: Well, Alice, I tried my best to learn more about Yoshida's algorithms.

Alice: Tell me!

Bob: The good news is: I learned a lot more, and I even managed to construct

an eighth-order integrator, following his recipes. I also wrote a fourth-order

version, which is a lot simpler, and easier to understand intuitively.

Alice: A lot of good news indeed. What's the bad news?

Bob: I'm afraid I couldn't really follow the theory behind his ideas,

even though I was quite curious to see where these marvelous recipes came

from.

I went back to the original article in which he presents his ideas,

Construction of higher order symplectic integrators, by Haruo

Yoshida, 1990, Phys. Lett. A 150, 262. The problem for me was

that he starts off in the first paragraph talking about symplectic

two-forms, whatever they may be, and then launches into a discussion

of non-commutative operators, Poisson brackets, and so on. It all has

to do with Lie groups, it seems, something I don't know anything about.

To give you an idea, the first sentence in his section 3, basic formulas,

starts with ``First we recall the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula''.

But since I have never heard of this formula, I couldn't even begin to

recall it.

Alice: I remember the BCH formula! I came across it when I learned

about path integrals in quantum field theory. It was an essential

tool for composing propagators. And in Yoshida's case, he is adding a

series of leapfrog mappings together, in order to get one higher-order

mapping. Yes, I can see the analogy. The flow of the evolution of a

dynamical system can be modeled as driven by a Lie group, for which

the Lie algebra is non-commutative. Now with the BCH formula . . .

Bob: Alright, I'm glad it makes sense to you, and maybe some day we can sit

down and teach me the theory of Lie groups. But today, let's continue our

work toward getting an N-body simulation going. We haven't gotten further

than the 2-body problem yet. I'll listen to the stories by Mr. Lie some

other day, later.

Alice: I expect that these concepts will come in naturally when we start

working on Kepler regularization, which is a problem we'll have to

face sooner or later, when we start working with the dynamics of a thousand

point masses, and we encounter frequent close encounters in tight

double stars.

Bob: There, the trick seems to be to map the three-dimensional Kepler problem

onto the four-dimensional harmonic oscillator. I've never heard any mention

of Lie or the BCH formula in that context.

Alice: We'll see. I expect that when we have build a good laboratory,

equipped with the right tools to do a detailed exploration, we will find

new ways to treat perturbed motion in locally interacting small-N systems.

I would be very surprised if those explorations wouldn't get us naturally

involved in symplectic methods and Lie group applications.

Bob: We'll see indeed. At the end of Yoshida's paper, at least his

techniques get more understandable for me: he solves rather

complicated algebraic equations in order to get the coefficients for

various integration schemes. What I implemented for the sixth order

integrator before turns out to be based on just one set of his

coefficients, in what I called the d array, but there are two other

sets as well, which seem to be equally good.

What is more, he gives no less than seven different sets of coefficients

for his eighth-order scheme! I had no idea which of those seven to choose,

so I just took the first one listed. Here is my implementation, in the

file yo8body.rb

For comparison, let me repeat a run from our sixth-order experimentation,

with the same set of parameters. We saw earlier:

Here, let me make the time step somewhat smaller, and similarly the

integration time, so that we still do five integration steps. With a

little bit of luck, that will bring us in a regime where the error scaling

will behave the way it should. This last error may still be too large

to make meaningful comparisons

Alice: How about halving the time step? That should make the error

256 times smaller, if the integrator is indeed eighth-order accurate.

Bob: Here you are:

Bob: Now, even though I did not follow the abstract details of Yoshida's

paper, I did get the basic idea, I think. It helped to find his recipe

for a fourth-order integrator. I implemented that one as well. Here it

is:

Alice: Only three leapfrog calls this time.

Bob: Yes, the rule seems to be that a for an

Alice: Not only that, it even works for

Bob: You always like to generalize, don't you! But you're right, the

expression works for

Alice: And the fourth-order is indeed the first order for which the leaps

of the leapfrog are composed into a larger dance.

Bob: Perhaps we should call Yoshida's algorithm the leapdance scheme.

Alice: Or the dancefrog? Now, I would prefer the dancecat. you see,

cats are more likely to dance than frogs do. And while a cat is trying

to catch a frog, she may look like dancing while trying to follow the

frog.

Bob: Do cats eat frogs? I thought they stuck to mammals and birds.

Alice: I've never seen a cat eating a frog, but I bet that they like

to chase anything that moves; surely my cat does. Anyway, let's make

a picture of the fourth-order dance:

This is what your yo4 is doing, right? Starting at the bottom,

at time

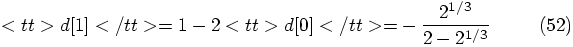

Bob: Yes, this is precisely what happens. And the length of the first

and the third time step can be calculated analytically, according to Yoshida,

a result that he ascribes to an earlier paper by Neri, in 1988. In

units of what you called

Alice: That will be easy to check. How about choosing somewhat different

values. Let's take a round number,

Bob: Good idea. Let me call the file yo8body_wrong.rb to make

sure we later don't get confused about which is which. I will leave the

correct methods yo4, yo6, and yo8 all in the

file yo8body.rb. Here is your suggestion for the wrong version:

Let's first take a previous run with the fourth-order Runge-Kutta rk4

method, to have a comparison run:

7.1. Recall Baker, Campbell and Hausdorff

7.2. An Eighth-Order Integrator

|gravity> ruby integrator_driver3h.rb < euler.in

dt = 0.1

dt_dia = 0.5

dt_out = 0.5

dt_end = 0.5

method = yo6

at time t = 0, after 0 steps :

E_kin = 0.125 , E_pot = -1 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 0

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-0

at time t = 0.5, after 5 steps :

E_kin = 0.232 , E_pot = -1.11 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 9.08e-10

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-1.04e-09

1.0000000000000000e+00

8.7155094516550113e-01 2.3875959971050609e-01

-5.2842606676242798e-01 4.2892868844542126e-01

My new eighth-order method yo8 gives:

|gravity> ruby integrator_driver3j.rb < euler.in

dt = 0.1

dt_dia = 0.5

dt_out = 0.5

dt_end = 0.5

method = yo8

at time t = 0, after 0 steps :

E_kin = 0.125 , E_pot = -1 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 0

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-0

at time t = 0.5, after 5 steps :

E_kin = 0.232 , E_pot = -1.11 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 4.2e-05

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-4.8e-05

1.0000000000000000e+00

8.7156845267947847e-01 2.3879462060443227e-01

-5.2848151560751322e-01 4.2888364744600843e-01

Significantly worse for the same time step than the sixth order case,

but of course there no a priori reason for it to be better or

worse for any particular choice of parameters. The point is that it

should get rapidly better when we go to smaller time steps. And it does!

|gravity> ruby integrator_driver3k.rb < euler.in

dt = 0.04

dt_dia = 0.2

dt_out = 0.2

dt_end = 0.2

method = yo8

at time t = 0, after 0 steps :

E_kin = 0.125 , E_pot = -1 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 0

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-0

at time t = 0.2, after 5 steps :

E_kin = 0.14 , E_pot = -1.02 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 7.5e-10

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-8.58e-10

1.0000000000000000e+00

9.7991592001699501e-01 9.9325555445578834e-02

-2.0168916703866913e-01 4.8980438183737618e-01

7.3. Seeing is Believing

|gravity> ruby integrator_driver3l.rb < euler.in

dt = 0.02

dt_dia = 0.2

dt_out = 0.2

dt_end = 0.2

method = yo8

at time t = 0, after 0 steps :

E_kin = 0.125 , E_pot = -1 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 0

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-0

at time t = 0.2, after 10 steps :

E_kin = 0.14 , E_pot = -1.02 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 2.82e-12

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-3.22e-12

1.0000000000000000e+00

9.7991591952094304e-01 9.9325554314944414e-02

-2.0168916469198325e-01 4.8980438255589787e-01

Not bad, I would say. I can give you another factor two shrinkage in time

step, before we run out of digits in machine accuracy:

|gravity> ruby integrator_driver3m.rb < euler.in

dt = 0.01

dt_dia = 0.2

dt_out = 0.2

dt_end = 0.2

method = yo8

at time t = 0, after 0 steps :

E_kin = 0.125 , E_pot = -1 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 0

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-0

at time t = 0.2, after 20 steps :

E_kin = 0.14 , E_pot = -1.02 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 9.77e-15

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-1.12e-14

1.0000000000000000e+00

9.7991591951908552e-01 9.9325554310707803e-02

-2.0168916468313569e-01 4.8980438255859476e-01

Alice: Again close to a factor 256 better, as behooves a proper eighth-order

integrator. Good! I believe the number 8 in yo8.

7.4. The Basic Idea

order

Yoshida integrator, you need to combine

order

Yoshida integrator, you need to combine  leapfrog leaps to

make one Yoshida leap, at least up to eighth-order, which is how far Yoshida's

paper went. You can check the numbers for

leapfrog leaps to

make one Yoshida leap, at least up to eighth-order, which is how far Yoshida's

paper went. You can check the numbers for  : three leaps

for the 4th-order scheme, seven for the sixth-order scheme, and fifteen for the

8th-order scheme.

: three leaps

for the 4th-order scheme, seven for the sixth-order scheme, and fifteen for the

8th-order scheme.

: a second-order

integrator uses exactly one leapfrog, and a zeroth-order integrator by

definition does not do anything, so it makes zero leaps.

: a second-order

integrator uses exactly one leapfrog, and a zeroth-order integrator by

definition does not do anything, so it makes zero leaps.

alright.

alright.

, you jump forward a little further than the

time step

, you jump forward a little further than the

time step  would ask you to do for a single leapfrog.

Then you jump backward to such an extent that you have to jump forward

again, over the same distance as you jumped originally, in order to

reach the desired time at the end of the time step:

would ask you to do for a single leapfrog.

Then you jump backward to such an extent that you have to jump forward

again, over the same distance as you jumped originally, in order to

reach the desired time at the end of the time step:  .

.

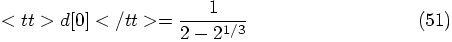

, it is the expression in the

first coefficient in the d array in yo4:

, it is the expression in the

first coefficient in the d array in yo4:

7.5. Testing the Wrong Scheme

, which forces

the other number to be

, which forces

the other number to be  . If there is a matter of

fine tuning involved, these wrong values should give only second-order

behavior, since a random combination of three second-order integrator

steps should still scale as a second-order combination.

. If there is a matter of

fine tuning involved, these wrong values should give only second-order

behavior, since a random combination of three second-order integrator

steps should still scale as a second-order combination.

|gravity> ruby integrator_driver2i.rb < euler.in

dt = 0.1

dt_dia = 0.1

dt_out = 0.1

dt_end = 0.1

method = rk4

at time t = 0, after 0 steps :

E_kin = 0.125 , E_pot = -1 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 0

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-0

at time t = 0.1, after 1 steps :

E_kin = 0.129 , E_pot = -1 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 1.75e-08

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-2.01e-08

1.0000000000000000e+00

9.9499478923153439e-01 4.9916431937376750e-02

-1.0020915515250550e-01 4.9748795077019681e-01

Here is our faulty yo4 result, for the same parameters:

|gravity> ruby integrator_driver3n.rb < euler.in

dt = 0.1

dt_dia = 0.1

dt_out = 0.1

dt_end = 0.1

method = yo4

at time t = 0, after 0 steps :

E_kin = 0.125 , E_pot = -1 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 0

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-0

at time t = 0.1, after 1 steps :

E_kin = 0.129 , E_pot = -1 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = -1.45e-05

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =1.66e-05

1.0000000000000000e+00

9.9498863274056060e-01 4.9808366540742943e-02

-1.0007862035430568e-01 4.9750844492670115e-01

and here for a ten times smaller time step:

|gravity> ruby integrator_driver3o.rb < euler.in

dt = 0.01

dt_dia = 0.1

dt_out = 0.1

dt_end = 0.1

method = yo4

at time t = 0, after 0 steps :

E_kin = 0.125 , E_pot = -1 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = 0

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =-0

at time t = 0.1, after 10 steps :

E_kin = 0.129 , E_pot = -1 , E_tot = -0.875

E_tot - E_init = -1.48e-07

(E_tot - E_init) / E_init =1.7e-07

1.0000000000000000e+00

9.9499471442505816e-01 4.9915380903880313e-02

-1.0020772164145644e-01 4.9748816373440058e-01

Alice: And it is clearly second-order. We can safely conclude that a

random choice of three leapfrog leaps doesn't help us much. Now how about

a well-orchestrated dance of three leaps, according to Neri's algorithm?