3. Tuning Ruby

Bob: Before we start adding pieces of C code to our Ruby code, let us

first see whether we can improve the speed of our N-body code purely

within the Ruby realm. As we discussed before, that should be the first

step, even though the second step, adding C, will buy us more in the end.

We may as well get extra speed from wherever we can.

Alice: So this means avoiding double work in pairwise interactions.

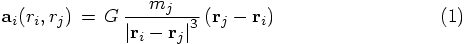

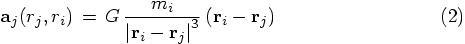

Bob: Exactly. What we have been doing so far was to let each particle

determine the acceleration it feels by interrogating all other particles.

However, the work done in calculating the gravitational acceleration from

particle j on particle i:

Alice: So you suggest rewriting our N-body code in such a way as

to allow both calculations to be done simultaneously.

Bob: Exactly.

Alice: That may not be so easy. Also, it may not be so pretty.

I like the modularity of our code, where each particle has its own

job to do in finding out how to determine the total gravitational

acceleration it feels from all other particles. I don't like the

idea of messing up everything by crossing levels of command.

Bob: And I don't like codes that are unnecessarily slow! At the

very least we have to try and find out. Only when we see what it

really looks like, and how much speed increase we really get, can we

decide whether the increas of speed is worth the decrease in

prettiness, however you may want to define that.

Alice: Fair enough.

Bob: I'll try to be careful with giving names to directories and files.

I must admit, I'm getting a bit confused with all the different versions

of N-body codes we now have lying around.

Alice: We should soon decide upon a library structure, where we can

store those versions we are really happy with.

Bob: Yes. Now that we have a rather versatile N-body code, a general

command line argument interpreter, and a generator for Plummer's model

realizations, we are beginning to put together a real N-body toolbox.

Well, one thing at a time. It is crucial that we get good speed out

of Ruby first. And in order to keep track of our N-body versions,

here is the file with the definitons of the Body and Nbody classes,

which we called rknbody.rb, after we had finished our command

line interpreter, in a directory I called vol-4. Our Plummer's

model building versions live in directory vol-5, so let me put

a copy of vol-4/rknbody.rb in the current directory vol-6,

and let me call it nbody1.rb, for short, with the 1

indicating that we'll probably make a few different versions, for our

various attempts at speedup.

Similarly, let me copy the driver from vol-4/rkn2.rb to the

current directory, and call it vol-6/nb1.rb, with the one

difference of course that the first line is no longer

Alice: You'd better keep some good notes! It is high time not only

for making a good library structure, but also for organizing our notes.

How are we ever going to present this to our students otherwise?

Bob: Yes, and we were going to define a good data format, remember, and

there is graphics, something we talked about many times, but never got

around too. People have no idea how much work it is to build a good

foundation for a software project. They think that an N-body code is

just integrating Newton's equations of motion, well, how complex can

that bed.

Alice: An understandable misunderstanding. Well, let's hope we can get

that misunderstanding out of the way, when we get our act together.

Bob: And no act without speedup. Here we go! I'm copying

nbody1.rb now to nbody2.rb, and in parallel I'm copying

nb1.rb to nb2.rb, with one distinction . . .

Alice: . . . again the first line.

Bob: Yes: instead of

Alice: No stopping you at this point!

Bob: I hope not. Give me a few minutes, and let me see how I can implement

a more economic pairwise acceleration calculation.

Alice: Hi Bob! How's your economic progress?

Bob: Fairly well, I think I just got it working. After scratching my head

for a bit, I realized that I had to move the method acc, to calculate the

acceleration between particles, from the Body to the Nbody class.

Alice: That's interesting, and a big change. But now that you mention it,

yes, of course: a single body can only care about it's own business.

It can calculate its own acceleration, but it wouldn't be able to help others.

Bob: Unless it had double pointers. Remember my first attempt at writing

an N-body code, way back after we had finished playing with our 2-body version?

You didn't like my backward pointers, but they would have enabled one particle

to talk directly to another particle.

Alice: Directly, you say? You mean by pointing back to the parent Nbody

class instance, and from ther to another particle, crossing boundaries twice!

If you can that direct, that you may as well flatten the whole organization

of the code into one big fat pancake . . .

Bob: . . . how can the pancake be fat and flat?

Alice: At partial attempt at flattening can still look wobbly and fat.

But my point is: such an approach would go against any attempt at modularity.

Bob: Okay, okay, I wasn't proposing to go back to that idea. For one thing,

I didn't look forward to having to argue with you about double crossing

pointers.

Alice: So you decided to lift the acceleration calculation from the Body

class to the Nbody class.

Bob: Yes. I've called it nb_acc now, instead of acc,

and it got a bit more complex, but not that much. Let me show them

side by side. Here is the old Body#acc, a somewhat confusing

Ruby notation meaning the acc method belonging to the class Body,

but we may as well get used to it, since it is in general use in the

Ruby community.

And here is Nbody#nb_acc, my new variation:

Alice: That's not much longer than what we had before. I see that

you start out by setting the acceleration to zero for each particle.

This means that every body now has an instance variable @acc,

on the same level as @pos and @vel, I take it?

Bob: Yes, and before doing any acceleration calculation, each particle's

@acc has to be set to zero, so that it can accumulate contributions.

A particle cannot delay this action until it starts to calculate its own

accelerations, since before doing so, it may already receive contributions

from other particles, as side effects of their calculations.

Alice: Then you enter into a double loop over particles, something that you

would normally code in an double for loop, using the traditional i and j

variables.

Bob: Yes, just as in the C test program, where we used:

Bob: Yes, I could have used

Alice: Remind me, what is the difference?

Bob: 1...3 counts over 1,2 only, while

1..3 counts over 1,2,3. The more dots, the fewer points.

I guess it the .. notation was chosen first as the most obvious

interpretation, and then ... was added as a practical after thought,

since it happens so often that we count through an array, starting at zero

and taking N terms, which means that we have to count up to but

excluding the Nth element.

Alice: You could have avoided mentioning the size of the array by

writing:

Alice: The rest of nb_acc is straightforward: after calculating

the usual r vector and r3 scalar values, you now get two

accelerations for the price of one. Can you show me what else you had to

change in the program?

Bob: I already mentioned the addition of an extra Body variable:

And the Body#calc method has simplified a lot. It used to be:

but in the new version it has become:

The reason for this trimming down is that all the hard work of acceleration

calculations are now done on the Nbody level. The only job left to do

on the Body level is to add, subtract terms containing

@pos and @vel and @acc, and multiply those with

coefficients and powers of the time step dt.

Consequently, the Nbody#calc method got trimmed down as well.

Instead of:

we now have:

Alice: Can you show me how this affect a simple integrator, such as

our forward Euler method?

Bob: It used to be:

while now we have:

You see, the line containing the acceleration is now much simpler, and

the whole expression is more homogeneous -- but of course you first have

to give the instruction to do the global acceleration calculation, something

that nb_acc takes care off.

Alice: And the other methods are affected similarly.

Bob: Yes, but with one exception. The two Runge Kutta methods are

changed the way would expect them to change. Here is the second-order one:

and here is the fourth-order version:

The exception comes in with the leapfrog method. I could have made a

similarly straightforward translation from the old version:

But I did not like to ask the whole system to calculate all

accelerations twice. You see, at the end of each loop, we change only

the velocity. This means that the acceleration calculation at the

beginning of the next step repeats exactly the same calculation as we

already did at the end of the previous, since the acceleration is only

dependent on the positions, not on the velocity. If we are interested

in speed-up, there is another potential factor of two in speed that we

can gain.

Alice: Let me try to remember, there must have been a reason that we

wrote it that way in the first place.

Bob: Yes, there was. You can't skip the second call to acc, since

otherwise @vel would not be properly updated at the end of the

step. But you can't skip the first call either, for two reasons.

The first reason has to do with start-up. When you take the very

first step, there is no previous information yet, so you just have

to calculate the acceleration at the beginning of the loop, in order

to step the position forward.

The second reason is connected with our previous approach of letting

each particle calculate its own acceleration, whenever needed, without

introducing extra variables unless we needed to do so. That made sense,

since we were aiming at clarity and brevity, rather than speed. But now

we have to reconsider those choices.

If we were to speed up the old approach, we would have to do two things:

acquire the initial acceleration in a special move at the start of an

integration, and introduce an extra variable @old_acc. However,

in our new approach, where we determine the integration on the Nbody

level for all particles at once, we already have the acceleration avaiable

immediately after a call to nb_acc, for each particle in the

variable @acc. So the only thing left to do is to warm up the

engine before getting into an integration loop.

Here is how I implemented this:

The flag init_flag tells you whether the acceleration variables

@acc have to be initialized. And that flag is set, you guessed

it, in the initializer for the Nbody system, since it is within the

Nbody class that the leapfrog method is used:

Alice: And in this way the initial nb_acc is invoked only

one time. That's a nice solution, which hardly complicates the

algorithm. And it is impressive that for the leapfrog we now have a

factor four in speed-up, at least with respect to the calculation of

pairwise gravitational attractions: we only visit each particle pair

once, instead of twice; and apart from the first round, each time the

frog leaps it calculations all accelarations only once. Great!

Bob: And that's it! No further changes needed.

Alice: You did not touch the calculation of the potential energy?

That is the only other place where there are operations that scale with

the square of the particle number.

Bob: One thing at a time. Normally we don't calculate the energy

of the system at every time step, but only when we ask for a diagnostics

output. Even if we lose a factor of two or four there, it will really

make no difference in the total speed.

This may chance when we start using C modules. If we really can get a

speedup of a factor 100 there, we may well have to revisit the energy

calculation too. Even if we calculate the energy, say, once every

thousand time steps, carelessness there could cost us a few tens of

percent in total speed.

Alice: I have one more suggestion for a change. Nothing to do with

speedup, only with making things look prettier. I bet you'll like it.

Bob: What do you have in mind?

Alice: Remember that you tried so hard to make the individual lines

of the integrators look as simple as they did, back in the days that

we were working on the two-body problem? Well, now that you have

brought the acceleration variables in line with the position and

velocity variables, we can finally grant yuor wish!

Let me try a bit of regular expression magic. May I?

Bob: Sure you may! As you know, I love brevity. But let me call

the new version nbody3.rb, to keep our versions separate. Here

is the keyboard.

Alice: It is the Nbody#calc that I would like to make just

a bit more smarter. In your last version it looked like this:

Are you ready for this? Here is a calc on steroids:

Bob: Ah, good old regular expressions! Let me see. Everywhere in the

string s you do two global substitutions, using gsub. First you take

any substring that starts with a lower case letter, followed by an arbitrary

number of alphanumeric characters -- the name of a variable, I take it.

Alice: Precisely.

Bob: Then you take that name, and you add a @ symbol in front

it in, because \& just echoes the previous match of what was

found in between the parentheses there, namely the variable name.

Ah, I get it! You add all those annoying @ signs that are

needed to tell Ruby that we are dealing with instance variables.

In that way we don't need to add those to the code of the integrators.

Alice, you're a genius!

Alice: maa, nee.

Bob: What does that mean?

Alice: Oh, I guess I didn't tell you that I started to take some

Japanese classes, just for fun. Occasionally I slip into classroom mode.

Just ignore that.

Bob: But then there is a second global substitution. Why that?

Let's see. Wherever you encounter an expression @dt, you replace

it by dt. Ah, of course. When you give every variable an

@ sign, it is all nice and well for pos to turn into

@pos, and so on, but you will also turn dt into

@dt, and that is too much of a good thing. Got it!

May I rewrite the integrators? That will be fun!

Alice: Go right ahead!

Bob: Let's see, almost a global replace of @ by nothing,

except for the @init_flag in leapfrog, almost trimmed

that one too, by mistake. Ah, that looks wonderful. Just look at

the fourth-order Runge Kutta:

What a beauty!

Alice: Glad you like it! 3.1. Pairing Pairwise Calculations

3.2. A Need for Library Structure

require "rknbody.rb"

but

require "nbody1.rb"

since we just changed the name of that file, even though the contents

are exactly the same.

require "nbody1.rb"

in nb1.rb, it now reads

require "nbody2.rb"

nb2.rb. I agree, there ought to be a better way. And I'm sure

there is. But first: speed!

3.3. From Body to Nbody

3.4. Looping Options

for (i = 0; i < n; i++)

for (j = i+1; j < n; j++)

Alice: It's interesting to see the options that Ruby offers. You could

have used for loops here too, of course.

for i in 0...@body.size

for j in i+1...@body.size

instead of

@body.each_index do |i|

(i+1...@body.size).each do |j|

I guess I'm growing fond of the each method that lets Ruby do the

counting, rather than having to worry explicitly about reminding myself

and the computer how long an array is, where to stop, and whether or not

to include the upper bound, using .. notation, or leave that

one out, using ....

@body.each_index do |i|

@body.each_index do |j|

if j > i

Bob: True, but since our aim is to speed up our calculations, I was

afraid that would get unnecessary overhead. Well, we can check later,

when we do our timings.

3.5. The calc Methods

attr_accessor :mass, :pos, :vel, :acc

def calc(time_step, s)

dt = time_step

eval(s)

end

def calc(s)

@body.each{|b| b.calc(@eps, @body, @dt, s)}

end

def calc(s)

@body.each{|b| b.calc(@dt, s)}

end

3.6. Integrators

3.7. The Leapfrog

def initialize

@body = []

@init_flag = true

end

3.8. Brevity

def calc(s)

@body.each{|b| b.calc(@dt, s)}

end

def calc(s)

@body.each{|b| b.calc(@dt, s.gsub(/([a-z]\w*)/, '@\&').gsub(/@dt/, 'dt'))}

end