2. N-Body Integrators

Alice: Yes, I get the idea, and that all makes a lot of sense.

And now that we understand how the data get read in, let's see what will happen

with them.

In rknbody1.rb, I see that you have shifted all the integration

methods from the Body to the Nbody class, as well as the evolve function

that calls them.

Bob: The evolve function orchestrates the whole integration process, and

it is called by the driver, which only knows about the one Nbody

instance that it has created. So it is logical to put the evolve

method inside the Nbody class. And since evolve calls the various

integration methods, it also seemed logical to have leapfrog,

rk2, and so on, reside there.

Alice: I could imagine an alternative, where each particle is given the

freedom to use its own integration method, in which case you would

want to shift those methods back into the Body class, but that would make

more sense when you use an individual time step algorithm, where each

particle has its own time step length. For the simple shared time step case

that we are starting with, your choice is surely the best.

Bob: I could imagine many things, but coding them takes more time than

imagining them! I do like the idea of relatively autonomous particles,

integrating themselves as they want, with stars in denser regions having

perhaps more specialized integrators, but not today.

Alice: Looking at evolve, I see almost exactly the same function that

we used for the two-body problem. The only difference is that now the

time is an instance variable for the Nbody class, which means that we

don't have to pass the time as an argument to the write_diagnostics

method.

Bob: Yes. If I would have left the time as a normal variable that would

be passed around, the evolve method would have been exactly the same.

A nice example of recycling code: whether you are dealing with one

pseudo particle or with N particles, the top level instructions are

basically the same.

Alice: But of course the actual work is different, and in our case more

complicated. The forward Euler implementation is a bit hard to recognize,

at first sight. Let me start with the new leapfrog method, which

looks more familiar. The two-body version was:

while now we have

This is easy to understand: for each body, basically the same actions are

taken as was the case for our single pseudo-body, containing the relative

position information for the two-body case.

Bob: The difference being that, invisibly at this level, the Body

method acc, which computes the acceleration, has to ask all other

particles for their position.

Alice: Indeed, acc has grown quite a bit bigger. In the two-body case,

we started with

and your new N-body version reads:

Bob: The main difference is the loop that our body has to execute over

all other bodies. It is here that I am using my backpointer @nb

that links back to the parent Nbody instance. In that way, the array of

bodies becomes visible for our particular body as @nb.body, and

it is this array over which we iterate using the familiar each construct.

Alice: And you are excluding the body itself from the loop, to avoid

getting an infinitely large self interaction, through the line:

But what exactly are you comparing? I am used to the C notation where

== compares two numbers. In Ruby too, when both numbers are

equal, the statement returns true, and if not, it returns false.

But what are the two numbers being compared here?

Bob: In Ruby, each object, that is each instance of any class, has a

unique id number, a machine-defined number that is guaranteed to be

different for two different objects. We don't have to know anything

about what that number is, or how it is represented. All we need to

know is that we can rely on it being different for two different

particles.

Alice: But this unique identification number has a different status

from that of normal numbers, such as integers or floating point numbers,

I presume. If I write a == b for two variables, Ruby compares

the values of these two variables, not their id numbers. If Ruby would

always use the == operator to compare object id numbers, then

a == b would always result in false, whenever the two

variables would be different, whether they have the same values or not.

Bob: Yes, you are right. I had not thought about that. In the case

of numbers, or strings for that matter, the == operator must

be overloaded so as to override the default behavior, which is

comparing id numbers. Interesting! I had just used this expression,

since it seemed reasonable, and does the right thing. But now that

you ask me, yes, there must be different types of overloading going on

for different classes. In other words, many different classes must

define their own == method.

Alice: The good thing about Ruby is that everything happens so

naturally, in such a transparent way. But a consequence is that you

often don't appreciate all that is going on behind the scenes. Coming

back to the statement above, this line is filtering out particle pair

combinations where both particles have the same identity.

Bob: Indeed. particles are not allowed to interact with themselves.

For all other particle pairs, we compute the acceleration in a similar

way as before. The main difference is that the vector connecting the

two bodies is not given, as was the case for the two-body problem,

where there was only one relative vector. Here we compute the vector

pointing from the calling particle to the called particle first, as

follows:

Alice: And the acceleration seems to have the same mass dependence

in both cases, the two-body and the N-body case, but here appearances

deceive: in the two-body case we had an equation of moment for our

pseudo particle, while here we are now dealing with real particles.

Bob: Yes, I thought about that carefully. Actually, the tricky thing is

to get the two-body case right, where it is easy to make a mistake, as we

saw when I was a bit too quick in coding up the diagnostics there.

For the N-body case, in contrast, it is all a piece of cake. The line

Directly implements Newton's law of gravity.

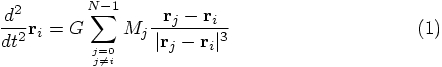

Alice: When we present this to our students, it would be good to summarize

the connection specifically. To wit: the expression for the

acceleration felt by particle i is given by summing together the

Newtonian gravitational attraction of all other particles j, where

both i and j take on values from 1 up to and including N, according

to the text books. In our case, of course, we label particles with numbers

starting from 0 and running up to and including N-1, since that

is Ruby's default way of numbering arrays. Let's write the equations

accordingly:

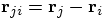

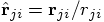

When I write this equation on a black board in front of a class, there

is always someone who asks me where the power of 3 in the denominator

comes from, given that Newtonian gravity is an inverse square law, and

therefore should be proportional to the power 2 of the distance, in

the denominator. To bring out the inverse square nature of gravity,

I then write

Finally, I note that the summation excludes self-interactions: every particle

feels the forces of the other

Bob: That's a nicely crisp summary.

Alice: What is really

nice in our Ruby implementation, is that we never have to introduce

the counters i and j that are so ubiquitous in any N-body code I have

ever seen. Just as we could dispense with the k variable for the

components of a vector, we can avoid the other two counters by asking

arrays and vectors to just loop over themselves.

And this is one of the features that makes Ruby eminently suited

for prototyping and development work in general. Whether Ruby will be used

eventually for an industrial-strength production-type code, that remains

to be seen.

Bob: If so, we'll have to do some very serious speed-up. My impression

so far has been that Ruby is at least a couple orders of magnitude slower

than the equivalent C or Fortran implementation.

Alice: In addition, our leapfrog calculates the acceleration twice

on the Nbody level, and for each particle pair, the relative acceleration

is also computed twice.

Bob: If we had been a little more clever, we would have saved a factor

of four there too. I bet we can speed up our code by a stunning factor of

a thousand or so, if we pull all stops!

Alice: Maybe, we'll see in due time. For now, I think we are being

clever, by not worrying at all about optimization. The point is to bring

out the underlying structure, which is complex enough all by itself. Once

we really see that clearly, we can start optimizing while avoiding confusing

clutter.

Bob: Note, by the way, one more difference between the 2-body and

N-body case: in the latter case we have to accumulate the results,

through the summation you just showed. Before traversing the loop

over particles, we have to clear the vector where the acceleration a

on our particle is being stored. I experimented with various ways to

do so, but the most compact notation I found was what I wrote on the top

of the acc method:

Isn't that a nifty and compact expression?

Alice: I see. In order to provide a null vector for the acceleration

with the right number of components, you use the position as a template,

and after copying the position, you fill all entries with zeroes. I'm

glad you put a comment line in, since otherwise the meaning wouldn't

have been so obvious at first reading.

Hmmm. While I agree that it is compact, perhaps a longer expression would

have been a bit more clear. How about

Alice: Yes, your construction was clever, but I'm still wondering about

the unsuspecting reader, who has to make sense of your cleverness. In fact,

in my more lengthy alternative, notice that I left your comment line

in, since upon first reading, even my longer line would still not be fully

clear, I'm afraid.

If I really wanted to be self-explanatory, I would write:

Bob: A long day, if you ask me. I would never have guessed your explanation

completely just from looking at that piece of code, so I would insert

a comment there as well -- which makes your alternative longer than mine.

I prefer to stick with my

Alice: Fine with me. This is really a matter of taste.

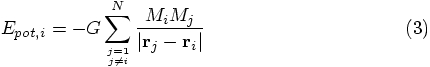

Bob: While we're at it, let me walk you through the rest of the Body

class definition. The potential is constructed in a very similar way

as the acceleration, by doing a body walk through the whole system.

In the two-body case, we started with:

My new N-body version reads:

The difference with respect to acc is that the potential energy

includes a product of the mass of the calling particle i and the

mass of the called particle j:

Bob: The rest of the input and output routines are unchanged, compared to

our earlier two-body code. Let's return to the Nbody class. You mentioned

that the leapfrog method was almost the same as before. Unfortunately,

that is the only one of our four integration methods that remained quite

simple to read. The other three have become a bit more crowded, I'm afraid.

Alice: I'll start with the forward Euler case again. In forward, you

have replaced the previous form

by:

Bob: This is a tricky point. Before we stored the original acceleration

in the vector old_acc, which was a single physical vector, containing

the relative acceleration between our two particles. In the N-dimensional

analogue that we have here, we need to store N initial acceleration vectors,

one for each particle.

The most straightforward solution would be to define a new instance variable

for the Body class, @old_acc, but I rejected that solution.

As you will be happy to hear, I wanted to keep the code modular, without

letting the Body class know what the Nbody class might decide to be

good algorithms. The alternative would be to saddle the poor Body class

simultaneously with all the possible variables that would be needed in all

the algorithms you could choose from.

Alice: I indeed applaud your desire for modularity. However, in this

particular case I'm not so sure whether we should insist on such a strong

separation. Let's get back to that in a moment.

Bob: Since I wanted to keep the auxiliary variables, such as

old_acc, local, I could not loop over them using the

@body.each construct used in leapfrog. Of course, you can

loop over old_acc alone easily enough, in a old_acc.each

construction, but that would in turn not allow the @body array

to be traversed.

The only solution I saw was to introduce an index i -- yes, I know,

we just celebrated the lack of indices i and j in Ruby, and I'm

not happy with it, but at least for now, it works. In that way, I

could use the Array method @body.each_index, which does

what it says it does, namely traversing the @body array.

Now since old_acc and @body have the same number of

components, equal to the number of particles N, this one construct

can simultaneously traverse both arrays. The i index is the glue

that connects both traversals, keeping them in lock step.

In addition, I had to introduce the array old_acc, which I

did here in the first line of forward. The third line did not

contain any local variables, so there at least I could avoid the use

of an i variable.

Alice: That is a reasonable solution. You are trading modularity for

readability. And while I'm sure there are several alternatives, let's

first complete our guided tour here. What is left to visit is the

energy diagnostics part of the code.

Bob: That turned out to be really simple. For each Body method

ekin there is a corresponding Nbody method ekin that gathers all

the individual results, and sums them up to find the total kinetic energy.

Here is the Body version:

and here is the Nbody version:

In order to sum it all up, I introduce a variable e, initialize it to

zero, add the various contributions, and then I list e again, in the

final line. In that way, the method ekin returns the correct value e.

Alice: Just curious: couldn't you have left out the last line, with the

single e? At the last time that the statement in the previous line will

be executed, some particle's kinetic energy will be added to e, so e

will be what is going to be returned anyway, no?

Bob: I'm not sure. You're talking about the last action in a loop, and

then control is being returned to the each method. But it is easy enough

to find out whether that would work. Let's call irb for help:

Bob: Well, I wasn't sure either. Learn something new everyday. And it is

certainly nice to work with an interpreted, rather than a compiled language:

this type of checking you can do extremely quickly and easily.

Alice: The story for the potential energy must be similar. For each particle

we have a method epot associated with the Body class, as you just

showed us already, and a method with the same name, but associated

with the Nbody class:

Just like for the kinetic energy, the Nbody method epot gathers

all the contributions to the potential energy of the various bodies --

with one twist: you are now dividing by a factor two. Ah, of course:

for each particle pair, the contribution is counted once when the one

particle computes its potential energy, and once again when the other

particle computes its potential energy. Therefore, every particle pair

contribution gets counted twice, and at the end we have to correct for that.

Bob: Yes, indeed. And yes, I had left that factor of two out, the first

time I ran the program. Diagnostics are wonderful; they sure keep you honest:

of course I could get no good energy conservation no matter what I tried,

until I realized what was going wrong. I found it by computing the initial

kinetic energy and potential energy for a two-body system, which was easy

enough to do on paper. Comparing it with the numerical result, it was

immediately clear that the potential energy was counted twice. 2.1. Inspecting the Leapfrog

def leapfrog(dt)

@vel += acc*0.5*dt

@pos += @vel*dt

@vel += acc*0.5*dt

end

2.2. Acceleration

def acc

r2 = @pos*@pos

r3 = r2*sqrt(r2)

@pos*(-@mass/r3)

end

2.3. Newtonian Gravity

and

and  are the mass and position

vector of particle j, and G is the gravitational constant.

are the mass and position

vector of particle j, and G is the gravitational constant.

, with

, with  ,

after which I define the unit

vector

,

after which I define the unit

vector  . This allows the

above equation to be written as:

. This allows the

above equation to be written as:

particles, but not its

own force, which, as we already mentioned, would be infinitely large

in case of a point mass.

particles, but not its

own force, which, as we already mentioned, would be infinitely large

in case of a point mass.

2.4. A Matter of Taste

a = @pos*0 # null vector of the correct length

a = ([0]*@pos.size).to_v # null vector of the correct length

Bob: Yes, that would bring out the fact that you use the position vector

only because you want to extract its size, and not for any other reason.

And you explicitly show how you start with an array of length 1,

filled with a single 0, and then extend that array to contain

@pos.size components. But then you still have to convert it into

a vector. You see, I avoided the last step by starting with a copy of

@pos, which was already a vector.

vector_size = @pos.size

a = ([0]*vector_size).to_v

That way I would express the fact that a is a vector, that it needs

to be of the right size, that it should contain all zeroes, and that

it should be converted to a proper vector at the end of the day.

a = @pos*0 # null vector of the correct length

2.5. Potential Energy

def epot # potential energy

-@mass/sqrt(@pos*@pos) # per unit of reduced mass

end

2.6. Local Arrays

def forward(dt)

old_acc = acc

@pos += @vel*dt

@vel += old_acc*dt

end

2.7. Energy Diagnostics

def ekin # kinetic energy

0.5*(@vel*@vel)

end

def ekin # kinetic energy

e = 0

@body.each{|b| e += b.ekin}

e

end

|gravity> irb

irb(main):001:0> a = [1, 2, 3]

=> [1, 2, 3]

irb(main):002:0> e = 2

=> 2

irb(main):003:0> a.each{|b| e += b}

=> [0, 1, 2, 3]

irb(main):004:0> e

=> 8

Alice: I see. You were correct in worrying about the control coming back

to the array. Actually, that makes sense: it was the array a in

this example that called the each method. And frankly, even if it

would have worked, it might have been better to leave the final e

line in there, at the end of your ekin, for clarity.