9. The WorldPoint Class

Bob: Now we come to the bottom of our hierarchy, where we find the

WorldPoint class, which is a subclass of the Body class:

Alice: We have defined three phases of operation, a setup phase,

a startup phase, and a normal phase in which we push particles forward.

The difference between there three is finally becoming clear now.

Bob: At startup, we are revving the engines, so to speak: we are

computing the initial force calculations, but we are not moving any

particle yet. The engines are running in place.

Alice: In a way, we are simulating a previous step, by leaving the

system in exactly the type of state it would have been in, had we arrived

at the initial time from a previous integration. To the extent that a

previous integration would have provided us with force calculations at

the end of a previous step, we are doing those force calculations now.

Bob: Now why did we not just combine the setup and startup routines?

Alice: Good question. Hmm. On this level there certainly does not seem

to be any clear reason not to combine these two. But we must have had

some reason. Let's go back to the next level up, to WordLine, where

these functions must be called from.

Ah, yes, there too we have two functions with the same name, setup

and startup. Hmm again. At this point, too, it seems clear that we

could have combined these functions. Well, let's keep moving up, to

the WorldEra level.

Bob: Ho, before we do that, notice that there is another setup related

method on the WorldLine level. At the very end, we have

setup_from_single_worldpoint. In that method, the worldpoint

itself is set up. Not that type of setting up surely has to be done

for each particle, before we can even think of starting up the force

calculation for each particle.

Alice: Perhaps we should have combined those two methods,

WorldLine#setup and WorldLine#setup_from_single_worldpoint.

Something to keep in mind for a future version. For now, let's leave this

version alone as it is, since it works.

Still, I'd like to see what happens on higher levels. I'll just do a search

for setup.

On the WorldEra level, the only thing that turns up is

setup_from_snapshot. Ah, this is in contrast with what we

just saw on the WorldLine level, where we set up a single word line

from a single world point, as the starting point. Here we setup the

whole system, starting from a whole snapshot.

Continuing the search for setup, here is the next function, now on

the top level, World#setup_from_world and

World#setup_from_snapshot.

Bob: The first one is almost trivial, since everything has already been

set up in the previous run; all we have to do is to set a few appropriate

variables and off we go. The second one, setup_from_snapshot,

is the interesting one. And hey, look, on the fifth line, we are doing

a form of startup, in startup_and_report_energy.

Alice: Now that is confusing. Definitely, in the next rewrite, I will

insist on separating setting up and starting up on all levels!

Bob: But as you already said, not today. We still have to go through the

WorldPoint class definition, remember! We've only looked at the

first two methods.

Alice: The rest should not contain too many surprises. The correct

step looks just like what we already had in nbody_ind1.rb:

all the coefficients are the same, as they should be, just the notation

is somewhat different.

But wait a minute, if we have a corrector here, what happened with

our predictor?

Bob: You have forgotten already? On the WorldLine level, we took

a single step as follows:

which indeed contains a predict step and a correct step. The correct

step is a direct invocation of WorldPoint#correct which we are

now looking at. And the predict step is given on the WorldLine level as:

This means that we should not look for a method WorldPoint#predict

but a method WorldPoint#extrapolate.

Alice: Hmm, not exactly what I would have expected. And I don't want to

rely on memory. The logic of the code should speak for itself!

Perhaps we should call WorldPoint#extrapolaten

WorldPoint#predict instead. But

no, that won't do either, since there are other places where we only want to

exrapolate. There we specifically want to call

WorldPoint#extrapolate and it would be confusing to have to

call WorldPoint#predict. Perhaps the best thing to do is to

introduce the name WorldPoint#predict as just a one line

method calling WorldPoint#extrapolate, as a kind of alias.

Bob: Not today! I'm sure that once you get started, your taste for

abstraction and modularity and what not will get you carried away. We'll

leave that for the next pass.

Where were we? The method admin is trivial, just does some bookkeeping.

And then we have extrapolate, which we just discussed. It does indeed

exactly what Body#predict_step did in nbody_ind1.rb.

The next method is interpolate. Ah, this is new.

Alice: Yes. We decided that we'd better be as accurate as we could

reasonably be with our interpolation. After all, the main reason to

interpolate is to construct snapshots that we then hand to a diagnostics

routine.

Bob: I thought the main reason to construct snapshots was to be able

to do force calculations.

Alice: True, but for those snapshots, we have to extrapolate particles;

excuse me, predict particle positions. This double meaning of predicting

and extrapolating is making things sound complicated.

Bob: I see. So while you're growing world lines dynamically, you're always

taking snapshots that are a bit ahead of every known world point. That makes

sense. But by the time you look back to do all the diagnostics for a completed

era, you use interpolation.

Alice: Exactly. And in order to get the most accurate energy estimate,

we may as well use all the information we have, from both world

points, before and after the time at which we want to interpolated.

Bob: And if we count parameters, we have computed acceleration and jerk

at each of the two world point. These four pieces of information can be

transformed into four quantities at one the points, for convenience, to

allow us to construct a Taylor series there, without loss of information.

This means that at that point we have the acceleration and jerk that were

already available, and we compute the next two derivatives, the snap and

crackle,

Alice: I don't remember exactly how we derived the equations here.

I'd feel more comfortable just to check them again.

Bob: I do remember that it was quite a bit of pen and paper work.

I'm not eager to do this again, given that we know it works.

Alice: I agree, everything does seem to work, in the sense that we get

good fourth-order scaling of errors, and that for small enough time

steps we get an accuracy that is close what you can expect, using

double precision. That is a pragmatic check, but I would like to

check also on a more theoretical level.

This does not mean that we have to rederive everything here.

All we have to do is to check that the equations given here

for the position and velocity in between the two worldpoints

actually reduce to the exact position and velocity of each

worldpoint, in the limit of minimal and maximal interpolation

during this interval.

Bob: Is that really enough? A straight line between the positions

at the two worldpoints would not be a good interpolation, yet it would

agree with the positions at either end.

Alice: You are right, I was a little to glib. I should have added

that we need to check whether the appropriate derivates at either end

have the correct values as well.

Bob: How many derivatives does it take to be `appropriate'?

Alice: Good question. Hmm. Let us derive the answer, from scratch.

To start with, we are dealing with a fourth-order integration scheme,

so we would like to see a fourth-order polynomial, an expression in

powers of dt with dt**4 as the highest power. Now what are

the precise conditions for the coefficients . . .

Ah, there is a simpler way. You see, the expressions for the

corrected position and velocities, given by the methods correct,

three methods above interpolate, provide fourth-order expressions

for the position and velocities, in terms of powers of dt. We may

as well reinterpret those equations as providing us the intermediate

values for position and velocity as well!

Bob: They look mightily second-order in dt. But yes, that's

because they have been cleverly written that way. If you express

everything in terms of a Taylor series at the beginning point, the

true fourth-order nature becomes clear. This is a trick similar to

the one that is employed for the leapfrog: that scheme looks

first-order, but is actually second-order. This one looks

second-order, but is actually fourth-order.

That much is fine. But how do you want to recycle these equations

to use them for interpolation?

Alice: The corrector makes one big step from one world point to

the next. What we need is a method to make a smaller step, starting

at the same world point, but moving a smaller distance in time. We

can use these equations, just by shrinking the time dt.

Bob: But how? These expressions rely on the fact that you know

the values of the acceleration and jerk both at the beginning point

and end point. If you know keep the beginning point the same, but

you place the end point somewhere in the middle of the interval, you

have no information any more about the acceleration and jerk at that

point. These two quantities had been computed, directly from Newton's

equations of motion and its derivative, only at the two given world

points.

Alice: True, we have to reconstruct the values for acceleration and

jerk that we would have measured there, had we decided to do so. And

we only have to do that to fourth order in accuracy in dt. What I

did when I wrote the interpolator, was to evaluate the snap and crackle

at the beginning of the interval, from the measured acceleration

and jerk values . . .

Bob: . . . and then to use that snap and crackle in turn in a

Taylor series to reconstruct the needed acceleration and jerk at the

end of the interval.

Alice: I could have done that, but that would not be necessary:

once you have the Taylor series at the beginning of the interval,

to sufficiently high order, you already have the interpolation formula

you were looking for!

Bob: So you've put those expressions in there, when we were creating

this code. I wonder why I couldn't remember them at all!

Alice: You were rebooting the server, and I had a copy on my laptop,

so I thought I might as well make myself useful too.

Bob: Useful indeed.

But wait a minute, I see a fifth order term at the end of the right

hand side expression for the interpolated position! It is

(1/144.0)*crackle*dt**5. What is that doing there?

Alice: I remember we had a good reason to add that one, but I agree,

strictly speaking, it is not needed. Well, let's just accept the fact

that we put it there, and see what happens when we check the equations.

Bob: But not only it is not needed, it is inconsistent! If you

differentiate the expression for wp.pos, you get the one for

wp.vel, term by term, except for the last term.

The coefficient for the fifth-order term in wp.pos should have

been (1/120.0), shouldn't it, in order to lead to the proper

last term in the velocity.

Alice: Yes, it should have been, if we had insisted to make the

velocity to be the exact derivative of the position. But given that

we only need the position to fourth order, this discrepancy does not

necessarily spell trouble. But your objection is well taken; let's

put in a note to remind ourselves to get back to it.

Bob: Fair enough.

Alice: Let us start now by checking whether I

did my home work correctly. If so, the method interpolate

should reproduce the correct position and velocity values for the

world point other, if we take dt to be exactly the difference in

time dt = other.time - @time between the two world points.

Bob: But that is already the value we have chosen, in line 7!

Where do we use the value t? Ah, I see, further down, in line 10,

we change the value of dt to be t - time.

Alice: That's quite confusing. We'd better introduce a different

notation for the first dt, perhaps call it

Bob: That might be better, but as we said before, we're now analyzing

the code, and let us postpone changes for later.

Alice: Anyway, to check whether the interpolator lands correctly

on the end point, we actually equate these two forms of using dt.

So let's get started. The values associated with the world point

self, and given by instance variable names starting with a @,

are the values at the beginning of the step. Let us indicate those

with a subscript 0. The values at the end of the step, associated

with the world point other, I will give a subscript 1. We then

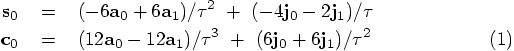

get the following notation, if we use

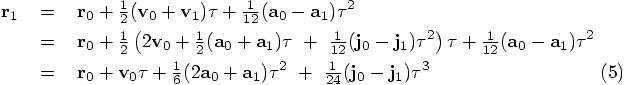

We then get:

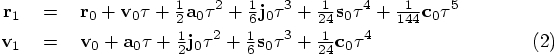

So far so good! Time to look at the first

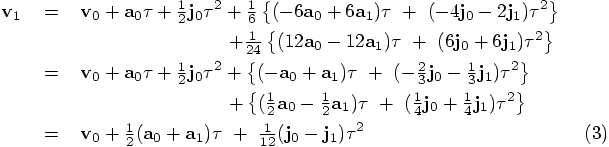

line of eq. (2), again substituting eq. (1):

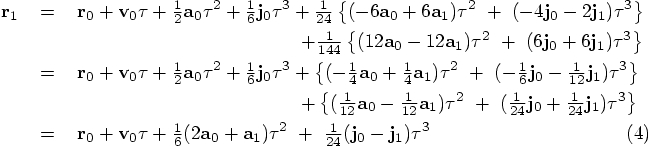

It is probably easiest to translate that expression directly into our

notation, after which we can substitute eq. (2):

Bob: Apart from the inconsistency in the fact that the derivative of the

position is no longer exactly what it should be.

Alice: You mean the fact that the last term in the first line of

eq. (2) has a coefficient of 1/444, rather than 1/120?

Bob: Yes. You told me you would get back to that.

Alice: Well, we now can find the reason. It would be nice to keep the

expressions for position and velocity consistent, in that you retrieve

the velocity by differentiating the position with respect to time.

At the same time, it would be nice to guarantee that the interpolation

formula gives you the correct values for both position and velocity,

at the beginning and at the end of the interpolated time interval.

Bob: And we now see that we cannot do both.

Alice: Exactly. Note, however, that we can do both on the level of

a fourth-order approximation. This inconsistency shows up only at fifth

order in

To be specific, in the first line of eq. (2), we could

have left out the last term altogether. In that case, we would be

fourth-order consistent, and you would be granted your wish: to this

order of accuracy, indeed the velocity would be the time derivative of

the position. But we our interpolation formula would be off by

exactly that last term, when we would ask for the position of the

interpolation at the end of the interpolated interval.

Bob: So in the end, it is mostly a matter of taste, whether we mind to

have fifth-order discontinuities in interpolated position, as a

function of time, in a fourth-order scheme, or whether we mind having

the velocity and the time derivative of the position being off by a

fifth-order term.

Alice: Well summarized. And I guess that is the penalty of having any

finite precision: if you are accurate to

Bob: I'm happy with the current choice, to keep the interpolator

fifth-order accurate in position. But it was a good exercise to check

exactly what we did and why. 9.1. Down at the Bottom

9.2. Setting Up and Starting Up

9.3. Predicting and Correcting.

and

and  , from the

two accelarations and jerks we have at hand. Got it!

, from the

two accelarations and jerks we have at hand. Got it!

9.4. Interpolation

9.5. Derivation

, and

use dt only for the last two lines.

, and

use dt only for the last two lines.

for the

interval dt, and translate the four lines for snap, crackle,

wp.pos, and wp.vel:

for the

interval dt, and translate the four lines for snap, crackle,

wp.pos, and wp.vel:

@vel = old_point.vel + (1/2.0)*(old_point.acc + @acc)*dt +

(1/12.0)*(old_point.jerk - @jerk) dt*2

@pos = old_point.pos + (1/2.0)*(old_point.vel + @vel)*dt +

(1/12.0)*(old_point.acc - @acc) dt*2

9.6. Glitches

.

.

order,

you will make errors on the

order,

you will make errors on the  order, in all

kinds of ways.

order, in all

kinds of ways.