19. Time Reversibility

Dan: I must agree, that is all very nice and clean. But let's get back

to the behavior of the two second-order algorithms that we have coded up

so far. Time symmetry is supposed to prevent a long-term drift. I'd like

to test that a bit more.

Let me take the modified Euler code, copying it from

euler_modified_vector.rb to

euler_modified_long_time.rb.

I will let the code run ten times longer, by changing the loop defining line

to:

Carol: I'm glad you're getting the hang of using long names. Thank you!

Dan: My pleasure. But see, I did still abbreviate a bit: I could have

left the word vector in, but that really would have made the

name too long, for my taste.

On a more important topic, I really don't like having different files lying

around that are almost the same, except for just one extra 0 in one line.

Carol: We'll have to do something about that. I had already been thinking

about introducing command line arguments.

Erica: What does that mean?

Carol: We really would like to specify the number of steps on the command

line, as an argument. It would be much better if we could take the program

euler_modified_vector.rb and run it for 10,000 steps, simply by

invoking it as

Dan: I would like that much better! Let's put that on our to-do list.

But for now, let me finish my long time behavior test. I'll write

leapfrog_long_time.rb, by modifying leapfrog.rb

in the same way, to take 10,000 steps:

Our expectation would be that modified Euler will completely screw up,

while the leapfrog will keep behaving relatively well. Let's see what

will happen!

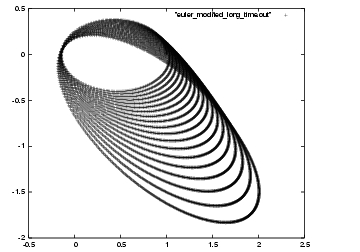

First I will make a picture of the long run for modified Euler,

in figure 39:

19.1. Long Time Behavior

|gravity> ruby euler_modified_vector.rb -n 10000

to indicate that now we want to take that many steps, or probably even

better

|gravity> ruby euler_modified_vector.rb -t 100

to indicate that we want to run for 100 time units.

|gravity> ruby euler_modified_long_time.rb > euler_modified_long_time.out

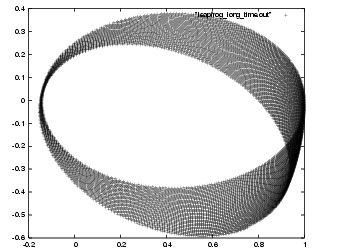

Next, I will make a picture of the long run for our leapfrog,

in figure 40:

|gravity> ruby leapfrog_long_time.rb > leapfrog_long_time.out

19.2. Discussing Time Symmetry

Carol: Your expectation was right, to some extent. Modified Euler is almost literally screwing up: the orbit gets wider and wider. In contrast, the leapfrog orbit keeps the same size, which is better for sure, but why does the orbit rotate?

Erica: Well, why not? A time symmetric code cannot spiral out, since such a motion would increase the size of the orbit. If an algorithm lets an orbit grow in one direction in time, it lets the orbit grow when applied to the other direction in time as well, as so it would not be time symmetric. However, if an orbit rotates clockwise in one direction in time, you might expect the orbit to rotate counter-clockwise in the other direction in time. So time reversal will just map a leftward rotation of the whole orbit figure into a rightward rotation, and similarly rightward into leftward

Dan: I don't get that. What's so different about expanding and rotating?

Erica: The key point is that we already have a sense of direction, in our elliptic Kepler orbit. Our star moves counter-clockwise along the ellipse, and we see that the leapfrog lets the whole ellipse slowly rotate clockwise. This means that if we let our star move in the other direction, clockwise, then the leapfrog would let the whole ellipse turn slowly in counter-clockwise direction. So the leapfrog algorithm would remain time symmetric: revolve within the orbit in one direction, and the whole orbit rotates; then revolve back into the other direction and the orbit shifts back again, until it reaches the original position.

However, during the course of one revolution, the orbit neither shrinks nor expands. Since there is no prefered direction, inwards or outwards, there is nothing for the leapfrog algorithm to capitalize on. It it were to make an error in one direction in time, say expanding the orbit, it would have to make the same error when going backward in time. So after moving forward and backward in time, during both moves the orbit would have expanded, and there is no way to get back to the original starting point. In other words, that would violate time symmetry.

Dan: Hmmmm. I guess. Well, let's first see how well this time

symmetry idea pans out in practice. Clearly,

nothing stops us from running the code backward.

After taking 10,000 steps forward, we can reverse the direction

by simply changing the sign of the time step value. I will do

that, and I will omit the print statement in the forward loop,

so that we only get to see the backward trajectory. If I would

print everything on top of each other, we probably wouldn't see

what was going on.

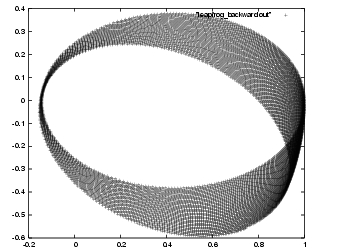

I will call the new code leapfrog_backward.rb, which is the

same as the old code leapfrog_long_time.rb, except that I

have replaced the original loop by the following two loops:

I will plot the backward trajectory in figure 41:

19.3. Testing Time Symmetry

|gravity> ruby leapfrog_backward.rb > leapfrog_backward.out

Carol: Figure 41 looks exactly the same as

figure 40!

Erica: Ah, yes, but that's precisely the point. The stars are retracing their steps so accurately, we can't see the difference!

Dan: Let's check how close the stars reach their point of departure, after their long travel:

|gravity> ruby leapfrog_backward.rb | tail -1 0.999999999999975 -1.06571782648723e-12 0.0 2.12594872261995e-12 0.500000000000013 0.0Wow, that's very close to the initial position and velocity, which we specified in our code to be:

r = [1, 0, 0].to_v

v = [0, 0.5, 0].to_v

Carol: But shouldn't the velocity have the opposite sign, now that

we're going backward?

Dan: No, I've gone back in time, using negative time steps, while

leaving everything else the same, including the sign of the velocity.

I could instead have reversed the direction of the velocity, while

leaving the time step the same. That would mean that time would keep

flowing forward, but the stars would move in the opposite direction,

from time

In this case, the final position and velocity are:

Erica: It is remarkable how close we come to the starting point.

And yet, it is not exactly the starting point.

Carol: The small deviations must be related to roundoff.

While the algorithm itself is strictly time symmetric, in the real

world of computing we typically work with double precision numbers

of 64 bits. This means that floating point numbers have a finite

precision, and that any calculation in floating point numbers will be

rounded off to the floating point number that is closest to the true

result. Since the rounding off process is not time symmetric, it will

introduce a slight time asymmetry.

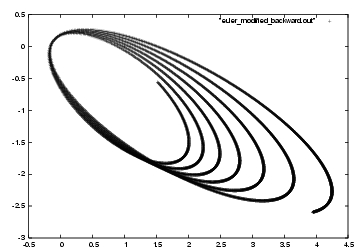

Dan: Before we move on, I'd like to make sure that the rival of

the leapfrog, good old modified Euler, is really not time symmetric.

I will do the same as what we did for the leapfrog.

I will call the new code euler_modified_backward.rb, which is the

same as the old code euler_modified_long_time.rb, except that I

have again replaced the original loop by these two loops:

I will plot the backward trajectory in figure 42:

19.4. Two Ways to Go Backward

to

to  . Let me try that

too, why not, in leapfrog_onward.rb. This code is the same

as leapfrog_backward.rb, with the only difference being the

one line in between the two loops, which now reads:

. Let me try that

too, why not, in leapfrog_onward.rb. This code is the same

as leapfrog_backward.rb, with the only difference being the

one line in between the two loops, which now reads:

|gravity> ruby leapfrog_onward.rb | tail -1

0.999999999999975 -1.06571782648723e-12 0.0 -2.12594872261995e-12 -0.500000000000013 -0.0

Carol: Indeed, now the velocity is reversed, while reaching the

same point. Great, thanks!

19.5. Testing a Lack of Time Symmetry

|gravity> ruby euler_modified_backward.rb > euler_modified_backward.out

Carol: Figure 42 looks nothing like

figure 39. Even when you reverse the

direction of time, the orbit just continues to spiral out, like

it did before. You have now definitely established

that the modified Euler algorithm is not time symmetric!

, with the

modified Euler algorithm, and step size

, with the

modified Euler algorithm, and step size  .

.

, with the

leapfrog algorithm, and step size

, with the

leapfrog algorithm, and step size  .

.

back to

back to  ,

and step size

,

and step size  .

.

back to

back to  ,

and step size

,

and step size  .

.