18. Leapfrog

Carol: Erica, we now have a second-order algorithm, modified Euler,

but you mentioned an other one, quite a while ago, that you seemed to prefer.

Erica: Yes, the leapfrog algorithm, a nice and simple scheme.

I just learned about that in class, so it is still fresh in my memory.

Dan: What a strange name. Does it let particles jump around like frogs?

Carol: Or like children jumping over each other?

Erica: Something like that, I guess. I never thought about the

meaning of the name, apart from the fact that something is leaping

over something, as we will see in a moment. The algorithm is used

quite widely, although it has different names in different fields of

science. In stellar dynamics you often hear it called leapfrog, but

in molecular dynamics it is generally called the Verlet method, and

I'm sure there must be other names in use in other fields.

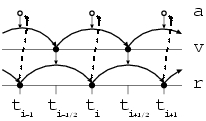

Here is the idea. Positions are defined at times

It is these positions and velocities that `leap over' each other.

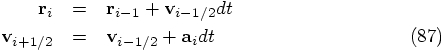

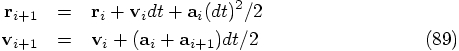

The leapfrog integration scheme reads:

Figure 37: With the leapfrog algorithm, when we update a position value to a new point

in time, we use the information from the velocity value in between the old

and the new point in time. This is indicated by the vertical downward

arrows. Similarly, when we update a velocity value to a new point

in time, we use the information from the acceleration value in between the old

and the new point in time. Each acceleration value is

computed directly from the position value, using Newton's law of gravity.

This is indicated with the dashed upward pointing arrows.

Erica: The simplest way to extrapolate the velocities from

Concretely, we can start with the initial conditions

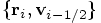

18.1. Interleaving Positions and Velocities

, spaced at constant intervals

, spaced at constant intervals  , while the velocities are defined at times halfway in

between, indicated by

, while the velocities are defined at times halfway in

between, indicated by  , where

, where  .

.

are defined only on

integer times, just like the positions, while the velocities are

defined only on half-integer times. This makes sense, given that the

acceleration on one particle depends only on its position with respect

to all other particles, and not on its or their velocities. To put it

in mathematical terms, for many situations in physics the acceleration

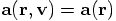

depends on velocity and position, as

are defined only on

integer times, just like the positions, while the velocities are

defined only on half-integer times. This makes sense, given that the

acceleration on one particle depends only on its position with respect

to all other particles, and not on its or their velocities. To put it

in mathematical terms, for many situations in physics the acceleration

depends on velocity and position, as  .

The motion of an electron in a magnetic field is one example, with the

Lorentz force being velocity dependent. And in any situation in which

there is friction, the friction is typically stronger for higher velocities.

However, in the case of Newtonian gravity, the velocity dependence is absent:

.

The motion of an electron in a magnetic field is one example, with the

Lorentz force being velocity dependent. And in any situation in which

there is friction, the friction is typically stronger for higher velocities.

However, in the case of Newtonian gravity, the velocity dependence is absent:

.

.

, how are you going to construct the velocities

at time

, how are you going to construct the velocities

at time  ?

?

to

to  is by using a Taylor series. and the simplest

nontrivial Taylor series is the one that takes only one term beyond the

initial value. It turns out that such utter simplicity is already enough!

is by using a Taylor series. and the simplest

nontrivial Taylor series is the one that takes only one term beyond the

initial value. It turns out that such utter simplicity is already enough!

and

and  , and take the first term in the Taylor series

expansion to compute the first leap value for

, and take the first term in the Taylor series

expansion to compute the first leap value for  :

:

,

using the first leap value for

,

using the first leap value for  .

Next we compute the acceleration

.

Next we compute the acceleration  , using Newton's

law of gravitation, and this enables us to compute the second leap value,

, using Newton's

law of gravitation, and this enables us to compute the second leap value,

, using the second line of apply

Eq. (87). In this way we just march on.

, using the second line of apply

Eq. (87). In this way we just march on.

Carol: And when you want to stop, or pause in order to do a printout, you can again construct a Taylor series in order to synchronize the positions and velocities, I presume? If you make frequent outputs, you'll have to do a lot of Tayloring around. I wonder whether that doesn't affect accuracy. Can you estimate the errors that will be introduced that way?

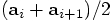

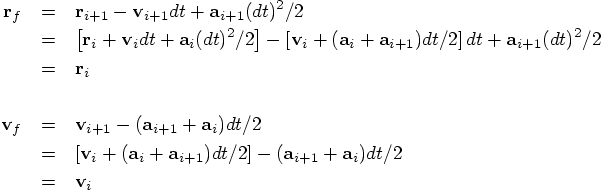

Erica: Ah, the beauty here is: you do not introduce any extra errors! In fact, what we usually do is never use the half-integer values for the velocity in any explicit way. Here, let me rewrite the basic equations of the algorithm, in such a way that position and velocity remain synchronized, both at the beginning and at the end of each step.

Erica: Ha, but looks deceive! Notice that the increment in

Dan: I'm still not quite convinced that Eq. (87) and

Eq. (92) really express the same integration scheme.

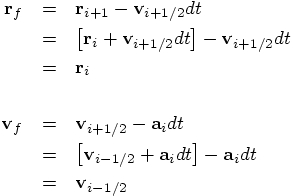

Erica: An interesting way to see the equivalence of the two descriptions

is to note the fact that the first two equations are explicitly

time-reversible, while it is not at all obvious whether the last two

equations are time-reversible. For the two systems to be equivalent,

they'd better share this property. Let us check this, for both cases.

Carol: Eq. (87) indeed looks pretty time symmetric.

Whether you jump forward or backward, in both cases you use the same

middle point to jump over. So when you first jump forward and then

jump backward, you come back to the same point.

Erica: Yes, but I would like to prove that, too, in a mathematical

way. It is all too easy to fool yourself with purely language-based

analogies.

Dan: Spoke the true scientist!

Carol: Well, I agree. In computer science too, intuition can lead you

astray quite easily. How do you want to check this?

Erica: Let us first take one step forward, taking a time step

We now have to inspect where the final positions and velocities

Don: Amazing indeed, but I would be really amazed if the same time

symmetry would hold for that other set of equations,

Eq. (92), that don't look time symmetric at all!

Erica: Yes, that's where the real fun comes in. The derivation

is a bit longer, but equally straightforward, and the steps are all

the same. Here it is:

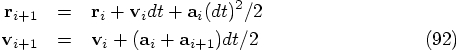

Dan: Okay, I'm convinced now that Eq. (92) does the

right thing. Let's code it up, and for convenience, let me write down

the equations again:

Let me see whether I'm getting the hang of using vectors now.

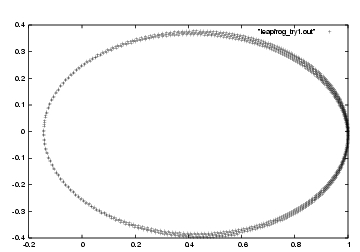

I will put it in file leapfrog_try1.rb:

and let me make a picture right away, in figure 38:

Erica: That is in fact an essential part of the leapfrog algorithm.

If it would drift in one direction, and if you would then play time

backward, it would have to drift in the other direction -- which means

it would not be time symmetric. So because the leapfrog is time

symmetric, it is impossible for the orbits to drift!

Dan: Ah, I just noticed something. In my leapfrog implementation,

I compute the acceleration at the end of the loop, and then at the

beginning of the next loop, I calculate the exact same acceleration

once again. Since the position r does not change between the two

calculations, the value of the acceleration a is bound to be the

same. That's a waste of computing time!

Carol: Well, for the two-body problem, we don't have to worry too much

about exactly how many milliseconds of computer time we are spending.

Erica: True, but when we go to a thousand-body problem, this will become

an issue. Good point, Dan, why don't you leave one of the acceleration

calculations out from the loop.

Dan: The question is, which one. If I leave out the first one,

the acceleration is not yet defined, when the loop gets transversed

for the very first time. But if I leave out the second one, I cannot

calculate the value of the velocity at the end of the loop.

Hmmm. The second acceleration calculation is clearly essential.

But . . . , aha, I see! I can take out the first acceleration calculation

and place it before the loop. That way, the length of the computer

program does not change. However, inside the loop unnecessary

calculations are no longer being done.

Here is the new version, in file leapfrog_try2.rb:

Let me check first to see that we get the same result. The first

code gives:

Carol: Let's check whether you really made the computation faster.

We can redirect the standard output to /dev/null, literally

a null device, effectively a waste basket, which is a Unix way of

throwing the results away. That way, we are left only with output

that appears on the standard error channel, such as timing information

provided by the time command.

The first code gives:

Carol: But we can make it even more clear, and we can make the loop

even shorter, with the help of our old friend, the DRY principle. Look,

the calculation for the acceleration, before and in the loop, contains

the exact same three lines. Those lines really ask to be encapsulated

in a method. Let me do that, in file leapfrog.rb:

and as always, I'll test it:

is given by the time step multiplied by

is given by the time step multiplied by

, effectively equal

to

, effectively equal

to  . Similarly, the increment in

. Similarly, the increment in

is given by the time step multiplied by

is given by the time step multiplied by

, effectively equal to the

intermediate value

, effectively equal to the

intermediate value  . In conclusion,

although both positions and velocities are defined at integer times,

their increments are governed by quantities approximately defined at

half-integer values of time.

. In conclusion,

although both positions and velocities are defined at integer times,

their increments are governed by quantities approximately defined at

half-integer values of time.

18.2. Time Symmetry

, to evolve

, to evolve  to

to

. We can then take one

step backward, using the same scheme, taking a time step of

. We can then take one

step backward, using the same scheme, taking a time step of

, back in time. Clearly, after these two steps the

time will return to the same value since

, back in time. Clearly, after these two steps the

time will return to the same value since  .

.

are indeed equal to

their initial values

are indeed equal to

their initial values  . Here is

the calculation. First we apply the first line of Eq. (87)

to compute

. Here is

the calculation. First we apply the first line of Eq. (87)

to compute  as the result of the step back in time,

and then we again apply the first line of Eq. (87), to

compute the forward step, and we see that indeed

as the result of the step back in time,

and then we again apply the first line of Eq. (87), to

compute the forward step, and we see that indeed

. Next we apply the second line of

Eq. (87) two times, to find that

. Next we apply the second line of

Eq. (87) two times, to find that

. Here is the whole derivation:

. Here is the whole derivation:

18.3. A Vector Implementation

to time

to time  , with both positions and

velocities.

, with both positions and

velocities.

|gravity> ruby leapfrog_try1.rb > leapfrog_try1.out

Carol: Now that is a clear improvement over modified Euler. Presumably

both schemes are second-order, but the orbit integration is clearly more

accurate in the case of the leapfrog. Modified Euler gave

figure (unknown label euler_modified_1000_steps_sparse) for the same time step size.

In fact, our leapfrog is almost as good as Modified Euler for a ten

times smaller time step, as given in

figure 33, in the sense that the

orbit does not drift away.

18.4. Saving Some Work

|gravity> ruby leapfrog_try1.rb | tail -1

0.583527377458303 -0.387366076048216 0.0 1.03799194001953 0.167802127213742 0.0

and the second version gives:

|gravity> ruby leapfrog_try2.rb | tail -1

0.583527377458303 -0.387366076048216 0.0 1.03799194001953 0.167802127213742 0.0

Good.

|gravity> time ruby leapfrog_try1.rb > /dev/null

0.352u 0.001s 0:00.38 92.1% 0+0k 0+0io 0pf+0w

and the second version gives:

|gravity> time ruby leapfrog_try2.rb > /dev/null

0.194u 0.000s 0:00.21 90.4% 0+0k 0+0io 0pf+0w

Dan: Indeed, a bit faster. If all the computer time would have

been spend on acceleration calculation, things would have sped up

by a factor two, but of course, that is not the case, so the speed

increase should be quite a bit less. This looks quite reasonable.

18.5. The DRY Principle Once Again

|gravity> ruby leapfrog.rb | tail -1

0.583527377458303 -0.387366076048216 0.0 1.03799194001953 0.167802127213742 0.0

.

.