9. Convergence for an Elliptic Orbit

Carol: Yes, let's go to smaller steps, but I'm worried about one thing,

though. Each time we make the steps ten times as small, we are generating

ten times more output. This means a ten times larger output file, and ten

times more points to load into our graphics figure. Something tells me

that we may have to make the steps a hundred times smaller yet, to get

reasonable convergence, and at some point we will be running into trouble

when we start saving millions of points.

Let's check the file size so far:

Erica: Good idea. A natural approach would be to keep the same number

of points as we got in our first attempt, namely one thousand.

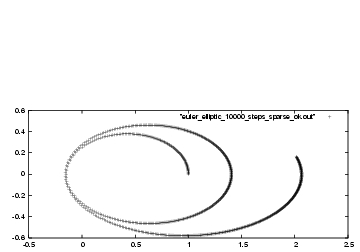

In our next-to-last plot, figure 22 you could still see

how the individual points were separated further from each other at the

left hand side, while in our last plot, figure 23,

everything is so crowded that you can't see what is going on.

Dan: What do you mean with `going on'?

Erica: In figure 22, on the left hand side, you can see

that the individual points are separated most when the particles come close

together. This means that the particles are moving at the highest speed,

which makes sense: when two particles fall toward each other, they speed up.

As long as we stick to only a few hundred points per orbit, we will be able

to see that effect nicely also when we reach convergence in more accurate

calculations.

Carol: I see. That makes sense. I'd like to aks you more about that,

but before doing so, let's first get the pruning job done, in order to

produce more sparse output. I will take our last code, from

euler_elliptic_10000_steps.rb, and call it

euler_elliptic_10000_steps_sparse.rb instead. Yes, Dan, you

can later copy it into ee1s.rb, if you like. How to prune

things? We have a time step of dt = 0.001 that is ten times

smaller than our original choice, and therefore it produces ten times

too many points.

The solution is to plot only one out of ten points. The simplest way I

can think of is to introduce a counter in our loop, which keeps track of

how many times we have traversed the loop. I will call the counter i:

Erica: what do the vertical bars mean?

Carol: That is how Ruby allows you to use a counter. In most languages, you

start with a counter, and then you define the looping mechanism explicitly

by using the counter. For example, in C you write

Dan: So now we have to give the print statements a test which is passed

only one out of ten times.

Carol: Exactly. How about this?

Here the symbol % gives you the reminder after a division,

just as in C.

Dan: So when you write 8%3, you get 2.

Carol: Yes. And the way I wrote it above, i%10, will be equal

to zero only one out of ten times, only when the number i is a multiple

of ten, or in decimal notation ends in a zero.

Dan: Okay, that's hard to argue with. Let's try it. Better make sure

that you land on the same last point as before. How about running the old

code and the new sparse code, and comparing the last few lines?

Carol: Good idea. After our debugging sessions you've gotten a taste

for testing, hey? You'll turn into a computer scientist before you

know it! I'll give you what you ordered, but of course there is hardly

anything that can go wrong:

Carol: . . . yes, I spoke too soon. The points do some to be further

separated from each other, but the last point from the new code doesn't

quite reach the last of the many points that the old code printed.

Ah, of course! I should have thought about that. Off by one!

Erica: Off by one?

Carol: Yes, that's what we call it when you forget that Ruby, or C for

that matter, is counting things starting from zero rather than from one.

The first time we traverse the loop, the value of i is zero, the second

time it is one. We want to print out the results one out of ten times.

This means that each time we have traversed the loop ten times, we print.

After the tenth traversal, i = 9, since we started with

i = 0. Here, I'll make the change, and call the file

euler_elliptic_10000_steps_sparse_ok.rb:

Let me try again:

Erica: I'd call it on target. And presumably the output file is

ten times smaller?

Carol: Easy to check:

Dan: Resulting in a sparser figure, I hope?

Carol: That's the idea!

Erica: And yes, you can again see the individual steps on the left-hand

side.

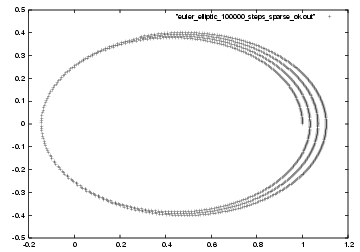

Carol: It will be easy now to take shorter and shorter steps.

Starting from euler_elliptic_10000_steps_sparse_ok.rb,

which we used before, I'll make a file

euler_elliptic_100000_steps_sparse_ok.rb,

with only two lines different: the dt value and the if statement:

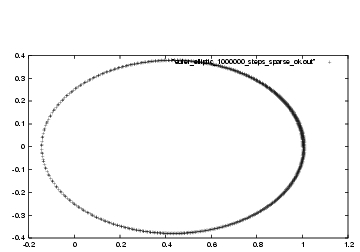

Similarly, in ruby euler_elliptic_1000000_steps_sparse_ok.rb we

have

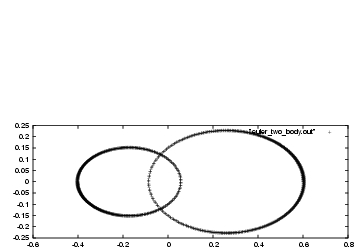

Dan: Beautiful. A real ellipse! Newton would have been delighted

to see this. The poor guy; he had to do everything by hand.

Carol: But at least he was not spending time debugging . . .

Erica: . . . or answering email. Those were the days!

Dan: I'm not completely clear about the asymmetry in the final

figure. At the left, the points are much further apart. Because

all points are equally spaced in time, this means that the motion

is much faster, right?

Erica: Right! Remember, what is plotted is the one-body system

that stands in for the solution of the two-body problem.

Carol: You know, I would find it really helpful if we could plot

the orbits of both particles separately. So far, it has made our

life easier to use the

Erica: That can't be hard. We just have to look at the summary

we wrote of our derivations, where was that, ah yes, Eq. (36)

is what we need.

Dan: And we derived those in Eqs. (22) and (24), because

Carol insisted we do so.

Carol: I'm glad I did! You see, it often pays off, if you're curious.

Pure science quickly leads to applied science.

Dan: You always have such a grandiose way to put yourself on the map!

But in this case you're right, we do have an application. Now how do

we do this . . . oh, it's easy really: we can just plot the positions

of both particles, in any order we like. As long as we plot all the

points, the orbits will show up in the end.

Erica: And it is most natural to plot the position of each particle

in turn, while traversing the loop once. All we have to do is to make

the print statements a bit more complicated.

Carol: But I don't like to do that twice, once before we enter the

loop, and once inside the loop, toward the end. It's high time to

define a method.

Dan: What's a method?

Carol: It's what is called a function in C or a subroutine in Fortran,

a piece of code that can be called from elsewhere, perhaps using some

arguments. Here, I'll show you. When you improve a code, rule number

one is: try not to break what already works. This means: be careful,

take it one step at a time.

In our case, this means: before trying to go to a new coordinate system,

let us first implement the method idea in the old code, then check that

the old code still gives the right result, and only then try to change

coordinate systems.

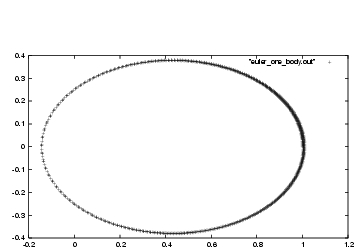

So far, we have solved the one-body system, using the computer program in

euler_elliptic_1000000_steps_sparse_ok.rb. I'll copy it to a

new file euler_one_body.rb. Now I'm going to wrap the print

statements for the one-body system into a method called print1:

and I will invoke this method once at the beginning, just before entering

the loop:

and once at the end of each loop traversal:

Dan: Wait a minute, shouldn't the if statement come in front?

Carol: in most languages, yes, but in Ruby you instead of writing:

Well, now this new code should give the same results as we had before:

Dan: If you really want to show that it's the same, why not print the last

lines in each case?

Carol: Right, let's check that too:

9.1. Adding a Counter

|gravity> ls -l euler_elliptic_10000_steps.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 makino makino 854128 Sep 14 08:04 euler_elliptic_10000_steps.out

Dan: I see, almost a Megabyte. This means that a thousand times smaller

step size would generate a file of almost a Gigabyte. That would be overkill

and probably take quite a while to plot. I guess we'll have to prune the

output, and only keep some of the points.

for (i = 0; i < imax; i++){ ... }

which defines a loop that is traversed imax times. Ruby is cleaner,

in the sense that it allows you to forget about such implementation details.

The construct

imax.times{ ... }

neatly takes care of everything, while hiding the actual counting procedure.

However, if you like to make the counter visible, you can do so by writing:

imax.times{|i| ... }

where i, or whatever name you like to choose for the variable, will become

the explicit counter.

9.2. Sparse Output

if i%10 == 0

print(x, " ", y, " ", z, " ")

print(vx, " ", vy, " ", vz, "\n")

end

|gravity> ruby euler_elliptic_10000_steps.rb | tail -3

2.01466014781365 0.162047884550843 0.0 -0.152387493429476 0.258735730522888 0.0

2.01450776032022 0.162306620281366 0.0 -0.152631496539003 0.258716104290758 0.0

2.01435512882368 0.162565336385657 0.0 -0.152875528688122 0.258696442895482 0.0

|gravity> ruby euler_elliptic_10000_steps_sparse.rb | tail -3

2.018682481674 0.155054729139203 0.0 -0.145810200248145 0.259252408016603 0.0

2.01721343061819 0.157646408310245 0.0 -0.14824383417573 0.259064012737983 0.0

2.01572003060918 0.160236187852851 0.0 -0.150680280478263 0.258872130993741 0.0

Dan: Well, hardly anything perhaps, but still something went wrong . . .

if i%10 == 9

print(x, " ", y, " ", z, " ")

print(vx, " ", vy, " ", vz, "\n")

end

|gravity> ruby euler_elliptic_10000_steps.rb | tail -3

2.01466014781365 0.162047884550843 0.0 -0.152387493429476 0.258735730522888 0.0

2.01450776032022 0.162306620281366 0.0 -0.152631496539003 0.258716104290758 0.0

2.01435512882368 0.162565336385657 0.0 -0.152875528688122 0.258696442895482 0.0

|gravity> ruby euler_elliptic_10000_steps_sparse_ok.rb | tail -3

2.01736143096325 0.157387325301357 0.0 -0.148000345061228 0.259083008888045 0.0

2.01587046711702 0.159977296376325 0.0 -0.150436507846502 0.258891476525706 0.0

2.01435512882368 0.162565336385657 0.0 -0.152875528688122 0.258696442895482 0.0

Dan: Congratulations! I guess this is called off by zero?

The last points are indeed identical.

|gravity> ruby euler_elliptic_10000_steps.rb | wc

10001 60006 854128

|gravity> ruby euler_elliptic_10000_steps_sparse_ok.rb | wc

1001 6006 85445

So it is; from more than 10,000 lines back to 1001 lines, as before.

9.3. Better and Better

|gravity> ruby euler_elliptic_10000_steps_sparse_ok.rb > euler_elliptic_10000_steps_sparse_ok.out

Here is the plot, in fig. 24.

if i%100 == 99

print(x, " ", y, " ", z, " ")

print(vx, " ", vy, " ", vz, "\n")

end

if i%1000 == 999

print(x, " ", y, " ", z, " ")

print(vx, " ", vy, " ", vz, "\n")

end

|gravity> ruby euler_elliptic_100000_steps_sparse_ok.rb > euler_elliptic_100000_steps_sparse_ok.out

|gravity> ruby euler_elliptic_1000000_steps_sparse_ok.rb > euler_elliptic_1000000_steps_sparse_ok.out

9.4. A Print Method

coordinates, since

we could choose the c.o.m. coordinate system in which

coordinates, since

we could choose the c.o.m. coordinate system in which

by definition, so we only had to plot

by definition, so we only had to plot

. But how about going back to our original

coordinate system, plotting the full

. But how about going back to our original

coordinate system, plotting the full  coordinates, one for each particle separately?

coordinates, one for each particle separately?

def print1(x,y,z,vx,vy,vz)

print(x, " ", y, " ", z, " ")

print(vx, " ", vy, " ", vz, "\n")

end

print1(x,y,z,vx,vy,vz)

1000000.times{|i|

print1(x,y,z,vx,vy,vz) if i%1000 == 999

if a

b

end

you can also write

b if a

if everything fits on one line, and then the end can be omitted.

|gravity> ruby euler_one_body.rb > euler_one_body.out

Erica: Sure looks the same.

|gravity> ruby euler_elliptic_1000000_steps_sparse_ok.rb | tail -3

0.496147378042769 -0.37881858244996 0.0 1.21129218162732 0.0849254022743251 0.0

0.508159065963217 -0.377892709335516 0.0 1.19108982655975 0.100148843547868 0.0

0.519970642634004 -0.376817992041834 0.0 1.17126787143698 0.114700879739653 0.0

|gravity> ruby euler_one_body.rb | tail -3

0.496147378042769 -0.37881858244996 0.0 1.21129218162732 0.0849254022743251 0.0

0.508159065963217 -0.377892709335516 0.0 1.19108982655975 0.100148843547868 0.0

0.519970642634004 -0.376817992041834 0.0 1.17126787143698 0.114700879739653 0.0

Dan: I'm happy. So now you're going to copy the code of

euler_one_body.rb to a new file called

euler_two_body.rb . . .

Carol: You're reading my mind. All I have to do now is implement

Eq. (36), and its time derivative, where positions are

replaced by velocities:

Dan: And change print1 to print2.

Carol: Yes, that plus the fact that I now have to give two

extra arguments, m1 and m2. In front of the loop

this becomes:

and at the end inside the loop:

Erica: But . . . don't we have to specify somewhere what the two masses

are?

Carol: Oops! Good point. So far we've been working in a system of

units in which

Erica: And for consistency, we should insist that the sum of the masses

remains unity, so we only have one value that we can freely choose. For

example, once we choose a value for m1, the value for m2

is fixed to be m2 = 1 - m1.

Carol: That's easy to add. How about making the masses somewhat unequal,

but not hugely so? That way we can still hope to see both orbits clearly.

I'll make m1 = 0.6:

Dan: Given that we use the convention

Erica: Yes, that is true. However, I prefer to keep print2

the way it is, just to make the physics clear. When you write

mfrac1*vx, it is clear that you are dealing with a velocity, vx,

that is multiplied by a mass fraction. If you were to write simply

m1*vx, you would get the same numerical value, but the casual

reader would get the impression that you are now working with a momentum,

rather than a velocity.

Carol: I agree. I can see Dan's argument for writing a shorter

and minimal version of print2, but I, too, prefer the longer

version, for clarity.

Dan: Okay, I can see the point, though I myself would prefer brevity

over clarity in this case. But since I'm outvoted here, let's leave

it as it is. Can you show the whole program? I'm beginning to loose

track now.

Carol: Here it is:

And here is the output:

9.5. From One Body to Two Bodies

print2(m1,m2,x,y,z,vx,vy,vz)

1000000.times{|i|

print2(m1,m2,x,y,z,vx,vy,vz) if i%1000 == 999

, and in the c.o.m. coordinates

we never had to specify what each mass value was. But now we'd better

write the mass values in the initial conditions.

, and in the c.o.m. coordinates

we never had to specify what each mass value was. But now we'd better

write the mass values in the initial conditions.

,

there is really no need to divide by this quantity, in the method

print2. In fact, there was no reason to introduce the

variables mfrac1 and mfrac2 for the mass fractions

that were assigned to each star. With the total mass being unity,

the mass fraction in each star has exactly the same value as the

mass of each star itself.

,

there is really no need to divide by this quantity, in the method

print2. In fact, there was no reason to introduce the

variables mfrac1 and mfrac2 for the mass fractions

that were assigned to each star. With the total mass being unity,

the mass fraction in each star has exactly the same value as the

mass of each star itself.

|gravity> ruby euler_two_body.rb > euler_two_body.out

And the results are plotted in fig. 28

Erica: Beautiful!

Dan: Indeed. That makes everything a lot more concrete for me. So the bigger ellipse belongs to the particle with the smaller mass, m2, and the smaller ellipse is for the bigger one, m1.

Erica: And they always face each other from different sides with respect

to the origin,  .

.

Carol: For now, I take your word for it, but it sure would be nice to see all that actually happening. I mean, it would be great to see the particles orbiting each other in a movie.

Erica: Definitely. But before we go into that, I suggest we move up one step, from the first-order forward Euler algorithm to a second-order algorithm. Look, we're now using a whopping one million steps just to go around a simple ellipse a few times. Clearly, forward Euler is very inefficient.

Dan: I've been wondering about that. I agree. Let's get a better scheme first, but then it will be time to see a movie.